After Bassano: Will Italian Export Titles Be More Reliable?

- Avv. Giuseppe Calabi

- Jan 8, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 4, 2025

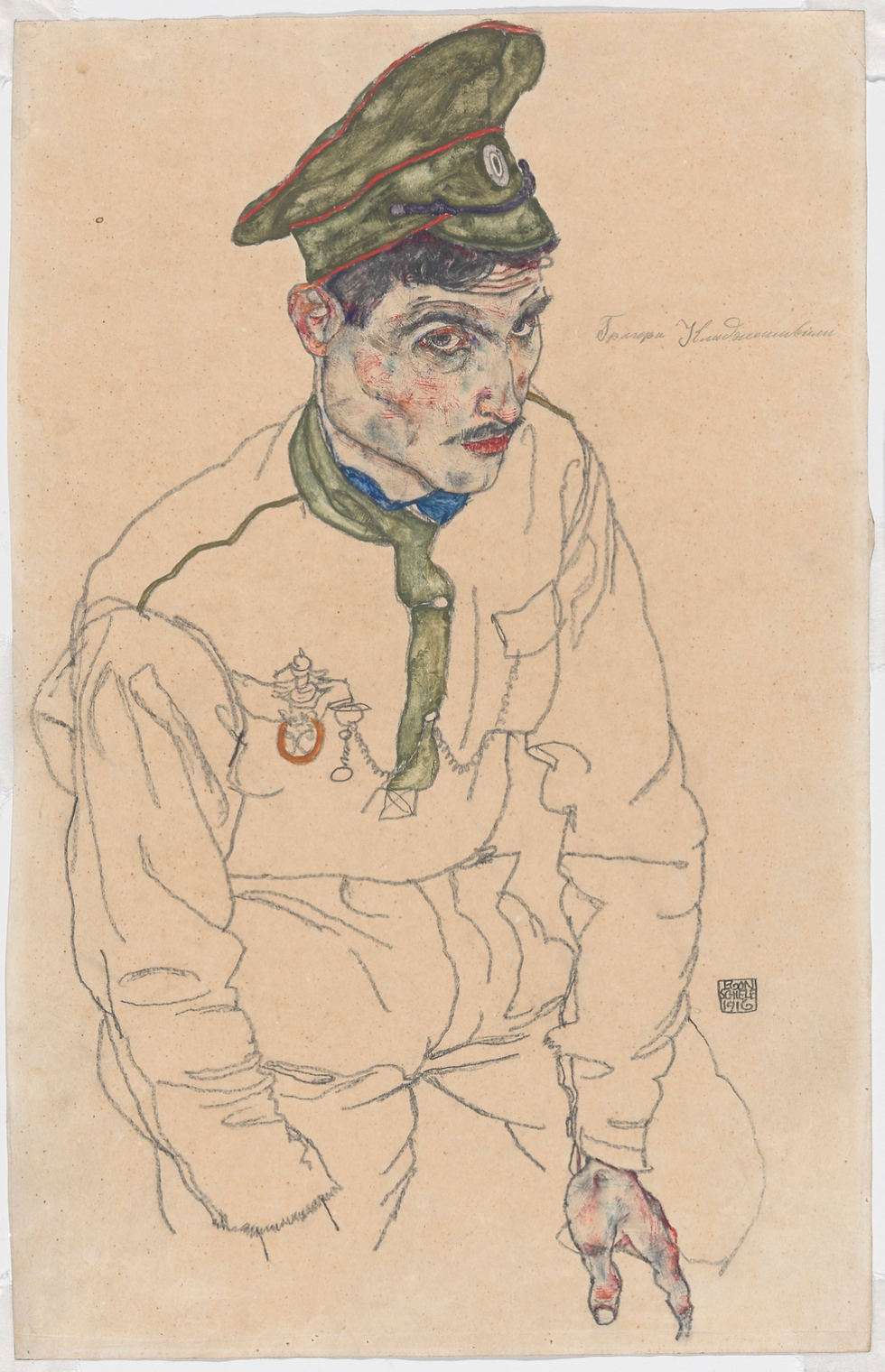

Jacopo Bassano, ‘The Miracle of the Quails‘, 1554

Can an Italian export licence be validly revoked many years after the painting has left Italy? A recent Italian Council of State ruling provides essential guidance.

Introduction

The Italian Council of State’s ruling of 21 November 2023, No. 9962 sets an important precedent for the regulation of the international circulation of cultural property in Italy.

These are the facts. In 2017, a Florentine antiquarian submitted an export permit application to the Pisa Export Office for a large painting depicting a biblical scene by Jacopo Da Ponte, a.k.a. Jacopo Bassano (Bassano del Grappa 1510-1592). After verification by three commissions, the Export Office issued a certificate of free circulation (domestic export licence). The Export Office also reduced the value declared by the exporting party (EUR 120,000) to EUR 70,000. After four years the painting was purchased by the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, which publicly announced its purchase. Shortly thereafter, at the urging of some social media users, who criticized the Ministry for allowing the export of a work deemed to be a masterpiece, the General Direction - Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape of the Ministry annulled the export licence and ordered the immediate repatriation of the painting to Italy.

The reason for the annulment and repatriation order was that the exporting party had failed to provide material information regarding the painting to the Export Office, or provided erroneous or even false information that led the Export Office to wrongly grant the licence.

Furthermore - according to the Ministry – the above anomalies could not have gone unnoticed by the Museum at the time of its purchase of the painting and, therefore, the good faith of the Getty was put into question by the Ministry. The Getty brought a claim against the Ministry requesting that the annulment of the export licence and the repatriation order be declared null and void. The Getty’s claim was dismissed by the Administrative Court of Rome. The Getty appealed and the Council of State overturned the first instance ruling, confirmed the validity of the export permit and found that both the exporting party and the Getty had correctly applied for and relied on the export licence, which was to be considered perfectly valid. The judgment by the Council of State is final ad binding and shall constitute an important precedent in Italian cultural property law.

The most relevant legal issues addressed by the Council of State, the Italian highest court for administrative law matters, are three: (1) what information the interested party should provide at the time of the export licence application; (2) under what conditions and within what timeframe the power of unilateral annulment of an export licence provided by Article 21-nonies of the Law 241/1999, i.e., the power to withdraw, with retroactive effect, a domestic export licence can be exercised; and (3) whether the disputed artwork by Jacopo Bassano could be subject to a heritage protection measure in consideration of its cultural relevance for the national patrimony.

1. Information at the Time of Filing the Export Licence Request.

Article 134 of Royal Decree No. 363 of 1913 provides that the following information be submitted to an Export Office at the time an export licence application is filed: the names of the owner and shipping agent, the shipping destination, the nature and description of the object to be exported.

Italian law also requires that the applicant declares the value of the artwork to be exported and the State can forcibly purchase it at the declared value. In this case the applicant had declared a value of EUR 120,000, which was reduced by the Export Office to EUR 70,000.

The Ministry has long advocated a broad interpretation of the above provision of the Royal Decree 363/1913, requiring the applicant to provide additional information, i.e. the date of the artwork, its author, the title or the subject matter represented in the artwork, its provenance, and bibliography. In the new online platform (SUE) adopted last 15th June, the provenance (previous owners/historical collections) and bibliography have been qualified as mandatory fields in the online application. In the present case, the Ministry considered that the indication “attributed to Bassano” made by the applicant, and the title of the work (“Biblical Subject”) were too generic or deceptive and were aimed at misleading the Export Office about the importance of the work. According to the Ministry, if the name “Jacopo da Ponte”, known as “Bassano”, had been mentioned as the author of the painting, and the specific theme depicted in the work (Fall of Quails or Partridges, or Fall of Manna, or Miracle of Partridges and Manna, Harvest of Partridges) had been correctly stated, and if the painting had been presented in a better conservation state, the Ministry would have denied the export licence. Moreover, the exporting party would have deceptively failed to indicate the provenance of the work and the related bibliography.

The Getty challenged this interpretation and argued that neither the royal decree 363/1913, nor any subsequent regulations give the public administration the power to require that the export licence applicant provide all the above information to the Export Office. The Council of State upheld the Getty’s argument and opined that:

“it is common knowledge that some information, for example the provenance of an artwork, is often not available to the owner, while the Export Office has or should have the necessary expertise to assess whether an artwork should be considered a relevant masterpiece for the national patrimony”.

For example, in case an artwork is purchased at auction or from a dealer, the name of the previous owner is never communicated to the buyer.

The Council of State rejected the Ministry's claim that the private collector had knowingly misled the administration by failing to provide relevant information.

According to the ruling, the request of export licence was not affected by false allegations or intentional omissions with a deceptive purpose, “since it could not be ruled out that the information provided by the applicant was consistent with the data plausibly in the possession of a private individual, who is normally less knowledgeable on the point than those institutionally charged with such delicate activities”.

2. The Time Limit for the Annulment of an Export Licence

The annulment of an export licence is permitted by law within a reasonable time limit. The law identifies the time limit of 12 months from the date the export licence is issued. This time limit is set as a reasonable criterion beyond which, the possibility of annulment of an export authorization is restricted to cases in which the licence was based on false representations of facts by the applicant or false or mendacious statements associated with the commission of a crime irrevocably ascertained by a final judgment. In such cases, an annulment of an export licence may occur even beyond the 12-month period. In the present case, the 12-month period had long elapsed, when - four years after the date of the licence - the Museum acquired the painting, and the Ministry cancelled the licence. The Council of State with its final judgment ruled out that the export application was affected by falsity or deceptive omissions (moreover, relating to non-mandatory information: provenance and bibliography) and, therefore, held that the annulment was not valid because it was not timely issued.

This principle is of fundamental importance because from now on Italian export titles will be characterized by greater stability, as they cannot be annulled years after their issuance.

It is foreseeable that foreign museums and collectors shall be more relieved when they decide to purchase artworks with an Italian provenance in accordance with an Italian export title because that shall be less exposed to a risk of unilateral cancellation of the export licence and subsequent repatriation order.

I am also convinced that the State of Council ruling will also greatly benefit the circulation and knowledge of Italian art and culture abroad.

Needless to say, this principle will not apply to cases in which fraudulent intent on the part of the exporter is proven by compelling evidence and not only asserted by the public administration.

3. The Cultural Importance of the Painting

The painting in question is undoubtedly an important painting and has also been recognized as such by the State Council. However, it should be noted that works by Bassano are widely present in Italian public collections (the Bassano del Grappa Museum alone has at least 15 paintings by Jacopo Bassano). All the important Italian museums, Brera and the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan, the Sabauda in Turin, the Estense in Modena, the Uffizi and Pitti in Florence, the Borghese, Corsini and Doria Pamphilj in Rome, and Capodimonte in Naples, can boast works by the artist.

If the work purchased by the Getty had been deemed important when the export licence application was submitted, the Italian State could have acquired it for the modest price of 70,000 euros and today it would be added (and perhaps go unnoticed compared to) those already in Italy. Is it not better that this painting can today be admired by millions of visitors to one of the most important museum institutions in the world?

Avv. Giuseppe Calabi

CBM & Partners Studio Legale

Blogs are written by Art Lawyers Association members and reflect their personal views. They do not represent the views of the Association

Comments